Finance 101 For Recent College Grads - Updated for 2020!

What Every College Grad Needs to Know About Investing/Saving... But No One Told You!

By Carey Nachenberg

So you’ve just graduated with your (Computer Science) degree, and if you’re like many of my students, you’re about to start a (six-figure) job… Yet you have no idea what to do with the gobs of money you’re about to make. What’s the best way to save for a new car, the eventual house, or even retirement?

Below are my suggestions – take them with a grain of salt! The following is just my opinion – not actionable advice – since everyone’s circumstances are different and every plan needs tweaking. So please do your own research before proceeding, and always talk with a trusted advisor (like your folks) before you make any decisions.

And one more thing before we begin - just remember that investing your money is a means and not an end. Your ultimate goal is to live a happy, balanced life - both during your working years and during retirement. So try to strike a balance between spending today, and saving for tomorrow. Thanks to Jimmy Kuo for reminding me of this super-important point.

Covid-19 Alert

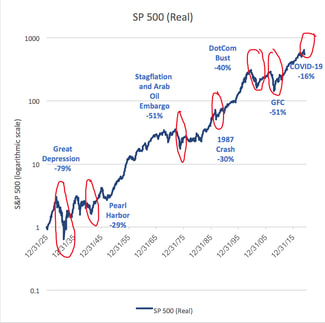

If you're freaking out about your recent stock losses due to the Covid-19 and wondering if things will ever return to normal, take a look at this graph of the stock market's performance over the past 100 years, and take heart. This too shall pass! Now back to the advice...

Step #0: Figure out how much you need for monthly expenses (and how much you want to save/invest)

The first thing you need to do is figure out how much money you’re going to need each year to pay for all of the essentials: housing, food, insurance, car payments, student debt payments, clothing, medical expenses, gym memberships, occasional entertainment, vacations, etc. Take 15-20 minutes to identify all of the major things you spend money on and create a spreadsheet with all of the details. We call these expenses your "living expenses."

Once you have an idea of how much you’ll need for essential living expenses each year, you can subtract this from your overall take-home pay (the amount deposited in your bank account after you pay all of your taxes) to determine how much money you’ll have left over to save/invest each year. This left-over money is called your investable assets. While you may want to splurge all of that left-over money on a really nice car or apartment, think twice. You should use those investable assets to save for retirement when you’re young, because the longer your money is invested, the more it will grow. Consider this: A recent grad that invests a single lump sum of $10,000 in the stock market when she’s 25 can expect to have around $288,000 by her 65th birthday! This assumes a 9% average compound growth rate, which is normal or even low for the US stock market, even with the market’s occasional crashes. Even with events like the Great Depression and Covid! Take a look at this graph of how well the US Stock Market (as represented by the S&P 500 index) has done through good times and bad:

What Every College Grad Needs to Know About Investing/Saving... But No One Told You!

By Carey Nachenberg

So you’ve just graduated with your (Computer Science) degree, and if you’re like many of my students, you’re about to start a (six-figure) job… Yet you have no idea what to do with the gobs of money you’re about to make. What’s the best way to save for a new car, the eventual house, or even retirement?

Below are my suggestions – take them with a grain of salt! The following is just my opinion – not actionable advice – since everyone’s circumstances are different and every plan needs tweaking. So please do your own research before proceeding, and always talk with a trusted advisor (like your folks) before you make any decisions.

And one more thing before we begin - just remember that investing your money is a means and not an end. Your ultimate goal is to live a happy, balanced life - both during your working years and during retirement. So try to strike a balance between spending today, and saving for tomorrow. Thanks to Jimmy Kuo for reminding me of this super-important point.

Covid-19 Alert

If you're freaking out about your recent stock losses due to the Covid-19 and wondering if things will ever return to normal, take a look at this graph of the stock market's performance over the past 100 years, and take heart. This too shall pass! Now back to the advice...

Step #0: Figure out how much you need for monthly expenses (and how much you want to save/invest)

The first thing you need to do is figure out how much money you’re going to need each year to pay for all of the essentials: housing, food, insurance, car payments, student debt payments, clothing, medical expenses, gym memberships, occasional entertainment, vacations, etc. Take 15-20 minutes to identify all of the major things you spend money on and create a spreadsheet with all of the details. We call these expenses your "living expenses."

Once you have an idea of how much you’ll need for essential living expenses each year, you can subtract this from your overall take-home pay (the amount deposited in your bank account after you pay all of your taxes) to determine how much money you’ll have left over to save/invest each year. This left-over money is called your investable assets. While you may want to splurge all of that left-over money on a really nice car or apartment, think twice. You should use those investable assets to save for retirement when you’re young, because the longer your money is invested, the more it will grow. Consider this: A recent grad that invests a single lump sum of $10,000 in the stock market when she’s 25 can expect to have around $288,000 by her 65th birthday! This assumes a 9% average compound growth rate, which is normal or even low for the US stock market, even with the market’s occasional crashes. Even with events like the Great Depression and Covid! Take a look at this graph of how well the US Stock Market (as represented by the S&P 500 index) has done through good times and bad:

And even if you can’t think that far ahead (to retirement at 65), think about the fancy house or condo you’ll want to buy in 5-10 years. To be prepared for both, you should try to save/invest at least 20%-25% per year of your total salary (before taxes are taken out). That means that if your salary is $100k/year, you’ll want to try to save a minimum of $20k/year, if not more. This may seem like a lot – especially after you see how much the government will take out for taxes – but you’ll be happy you lived a little bit simpler now, once you see the huge benefits you’ll get later.

To get an idea of how much money you’ll have to save each year to retire in comfort, try using an investment calculator like the one at Bankrate.com. You can specify how much money you have now, how much you plan to save each month, and when you plan to retire. The calculator will then determine how much money you’ll be able to take out from your savings each month during retirement, and how many years your savings will last before it runs out (eek).

Just remember, while a starting salary of $100,000 seems like a lot now, due to inflation, it’ll buy a lot less in 40 years. Consider this: A $100,000 salary in 40 years will have about the same buying power as $37,000 does today, assuming just a 2.5% rate of inflation (which is low by historical standards). So by the time you retire, if you’re used to living on $100k today, you’ll need $268k to achieve the same living standard! And by the way, after a few successful years in the high-tech industry, you’ll be very used to living on far more than just $100k per year. So it’s important to save now!

Step #1: Build up a 9-month emergency fund in a standard bank account (and pay down expensive debt)

You want to make sure you have a safety net should anything go wrong, so your first step is to start saving cash up in a standard, interest-paying checking or savings account. Calculate your average monthly living expenses (including rent, clothing, food, insurance, medical, etc.) and then over the next 3-9 months, sock away nine months worth of emergency funds in your bank account just in case the worst happens. Don’t touch this money – save it for a rainy day. And as your expenses go up, make sure to increase the amount in your emergency fund proportionally.

If you do have expensive credit card debt (credit card companies can charge 20% per year or MORE for debt you don't pay off!!!), then save up a few thousands dollars of emergency fund money - enough for any sudden emergency - and then begin paying off that credit card debt aggressively, perhaps applying 50% of what you can afford to paying down your credit card bill and saving 50% in your emergency fund. Until that high credit card debt is paid down, don't even think about the items below! As for student debt, unless it's at a super high interest rate, focus on building your emergency fund first (and the other items below) rather than aggressively paying student down.

Step #2: Enroll in your company’s 401K program and max-out your contributions

First, what is a 401K? A 401K is a government-sponsored retirement savings program. How does it work?

- Your employer has a relationship with a financial firm like E-trade, Charles Schwab, Fidelity or Vanguard.

- When you start working for your company, you create a new account with this financial firm.

- You then designate how much of your paycheck you want your company to auto-deduct and deposit into your account. You can designate up to $19.5k per year (as of 2020).

- Most (high-tech) companies will also “match” at least part of your contribution. What does this mean? Well, if you contribute at least a certain minimum amount to the account (e.g., $10k per year), your company will throw in an additional amount (e.g., $3k per year) to your account as an incentive for you to save. Free cash!

- You must then pick (from a limited menu provided by the financial firm) the set of of investments in which to invest your money – more on this below.

- When the time comes, you can withdraw money from the account to provide yourself with retirement income.

- Be careful: If you withdraw money before you reach retirement age, the government will slam you with nasty fees and/or taxes!

There are generally two types of 401K options: Regular 401Ks (pre-tax) and Roth 401Ks (post-tax). For the following two explanations, let’s assume you earn $100k per year.

Regular 401K – A Pre-tax Retirement Account: How it works

- When you sign up for the 401K plan with your company, you designate a certain amount to contribute to your Regular 401K account, e.g., $12k/year.

- Assuming you’ve designated $12k/year, your company will take out $1k per month from your paycheck and deposit it automatically in your Regular 401K account. If your company matches your contribution, they might add another $3k or more to your account each year as well! All of this money ($12k + $3k) is effectively off-limits to you – if you try to withdraw it from your Regular 401K account before retirement, you’ll have to pay nasty fees and taxes.

- Since you technically only received $88k in compensation from your company ($100k – $12k = $88k), the government treats this as your new total salary. It’s as if you only made $88k per year.

- Uncle Sam then taxes your income as if you made only $88k/year (not the full $100k). So if you pay 30% in taxes on this $88K, you’ll end up paying $26k and take home $62k per year in salary. Had you not invested in the 401K, you would have paid 30% on the full $100k, resulting in $30k of taxes to the government. Woohoo! You just saved $4k in taxes (but don’t worry, they’ll get you later when you pull the money out in retirement :))!

- Your investments in the Regular 401K grow and grow as time passes.

- When you reach retirement age, you begin withdrawing money from your Regular 401K account to live off of – this will be one of your primary sources of income.

- Since you never paid taxes on the money you contributed over the past 40-45 years (as well as any gains your investments made over that time), the government taxes every dollar you withdraw from your Regular 401K account just as if it were income from a regular job (only it’s income coming from your Regular 401K account instead). So if you withdrew $100k per year in retirement to live off of, and the tax rate were 30%, you’d have $70k per year off of which to live.

Roth 401K – A Post-tax Retirement Account: How it works

- When you sign up for the 401K plan with your company, you designate a certain amount to contribute to your Roth 401K account, e.g., $12k/year.

- Uncle Sam still taxes your full income of $100k per year. So, after federal and state taxes you might have $70k left (assuming a 30% tax rate on $100K/year).

- After taxes, your company takes $1k per month from your paycheck out of the remaining $70k, and deposits it automatically in your Roth 401K account, for a total of $12k saved per year. As before, your employer may also “match” your contribution and contribute another $3k-$6k to your Roth 401K account. Either way, your take-home pay is now $58k per year ($70k - $12k = $58k).

- Your investments in the Roth 401K grow and grow as time passes.

- When you reach retirement age, you begin withdrawing money from your Roth 401K account to provide you with a steady stream of income.

- Since you paid taxes on your income when you first earned it, the government does NOT tax the money (or any investment gains) within your Roth 401K account a second time when you withdraw the money in retirement! So if you withdrew $100k per year to live off of in retirement, you’d end up with the full $100k per year.

- In an emergency, you can also withdraw funds from your Roth 401K before your retirement age. You’ll need to pay some taxes on the money you withdraw, but this will be far less than the fees/taxes you’d have to pay if you prematurely withdraw your money from a Regular 401K.

So hopefully you see the difference. With a Regular 401K you pay taxes later – when you withdraw the funds in retirement. With a Roth 401K you pay taxes up front, then pay no taxes when you withdraw the funds in retirement.

So which should you pick? Well, if you think that taxes will be much higher in the future, then you should enroll in a Roth 401K. Then you’ll never pay a dime of tax on your 401K savings when you retire and withdraw the money. If, on the other hand, you think that taxes will be lower when you retire, then enroll in a Regular 401K. You can defer your taxes ‘til you retire. While no one can predict the future, I’m betting on taxes going up in the future (given our government’s ever-growing debt), so I’ve opted for a Roth 401K.

Another thing to consider is that you’ll likely be in a higher tax bracket when you retire, since your yearly income then will be much larger than your income as a recent grad today. You might think that everyone pays the same percentage of their salary, say 20%, for taxes. For example, if you made $50k per year, you’d pay $10k in taxes, and if you made $300k per year, you’d pay $60k in taxes. Unfortunately, you’d be wrong. In our US tax code, the government increases the percentage of money you pay in taxes as your income increases. If you make $50k per year (as of 2020), you’ll pay about 20% or $9.7k of your money in federal and state (California in this example) taxes. But if you make $300k per year, you’ll be in a higher tax bracket and have to pay a whopping 38% or $114k of your income in federal and state taxes! This is called progressive taxation, and it is likely to increase your tax rate during retirement… One more reason to choose a Roth 401K over a Regular 401K – all of that Roth 401K income will be un-taxable and not contribute to your overall income level (and thus not increase your tax bracket)!

Ok, so we've learned that it's a good thing to deposit a bunch of money into your 401K account. But a 401K isn't just a bank account that holds cash! Instead, it can hold one or more investments that you pick, and you get to decide how your money in the 401K account is invested. To do so, you will need to login to your 401K account (your employer will tell you how) and specify what investments your money should be used to buy.

So what is an investment? Some common investments that you may have heard of include stocks, bonds, precious metals (like gold), real estate, cash, etc. For example, if you buy 1,000 shares of Apple (AAPL) stock, that’s a stock investment. Another example of an investment is if you were to purchase a bond issued by the government or a corporation like Walmart. A bond is basically just a loan that a company/government takes from you, the bond buyer. When you buy a bond, you give the borrower (a company like Walmart or perhaps the California State Government) your money and they give you a bond in return. The bond is an IOU that promises to pay you back the full borrowed amount plus interest, e.g., 3% per year, after a predetermined amount of time, say 10 years. Each type of investment has its own risks and rewards. For example, just keeping cash is really safe, but you'll earn next to no interest so your savings won't grow (in fact, it'll actually shrink in value due to inflation). Buying stocks could result in growth of 10% per year or more, but stocks are risky and can also decline in a market crash. So there are pros and cons to each type of investment.

When you contribute your $19.5k/year to your 401K account, you have to designate how that money is invested within the account. Should your money be used to buy bonds from the California State Government to loan the state money to build new highways? Should your money be used to buy stocks like Apple (AAPL) and Amazon (AMZN)? Should it just be held as cash like in a bank account? Or should it be diversified - invested 60% in stocks, 20% in bonds, and 20% kept as cash? So once you begin your first job and you sign up for a 401K, you will need to log into your 401K account online and configure how your contributed money is to be invested. Don't forget to do this, because otherwise your employer will chose a set of default investments for you, and they're generally not that great (for example, avoid "target date retirement funds" if you're in your 20s)!

Typically, 401K plans offer you a fixed set of investment choices, and you have to choose wisely between them. For example, your 401K might give you five high-level choices: a large-cap stock index fund, a small-cap stock index fund, a bond index fund, a real-estate investment trust fund, and a money market fund (If you’re not sure what a "fund" is, see the Background on Stocks, Mutual Funds and Index Funds section below for more details). You then pick between those limited set of choices, e.g., "I want to invest 20% in the large-cap index fund, 15% in the small-cap index fund, 30% in the bond fund, etc." Once you make those choices, every new dollar that flows into the account over time will be invested based on those choices. The wrong choices could literally halve the amount of money you’ll have saved by retirement… or worse! Fortunately, the answer is generally pretty easy: If you’re in your twenties and not planning on retiring for 40+ years, you should invest all of the money in your 401K account in something called a Large Cap Stock Index Fund (there's more on what this is in the sections below). For example, if your company's 401K account is hosted by Vanguard, you could invest in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund (VFINX) or Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) - both are Large Cap Stock Index Funds.

Step #3: If you’re making under $124k/year (as of 2020), invest in a Roth IRA too!

While you can only invest a maximum of $19.5k/year in a Regular 401K or Roth 401k account, as it turns out, you can also invest an additional $5,500/year in something called a Roth IRA… but only if you make less than $124k per year (as of 2020). But be careful! This $124k cap includes ALL of your taxable income that you would report on your tax forms: your salary, gains from stocks sold in your private accounts, any stock shares you receive from your company that vested this year, bonuses, income you receive from renters, etc.

Unlike a 401K, which is provided and run by your employer, you have to set up a Roth IRA account on your own. To do so, go online to a firm like Vanguard, Charles Schwab or E-trade and follow their instructions to open a new Roth IRA account. IRA stands for Individual Retirement Account, and like a Roth 401K, you can use it to invest after-tax money for your retirement (you won’t pay taxes on your savings or the gains it makes when you pull the money out in retirement). So to clarify - your employer won't set up a Roth IRA for you - you’ll have to open and register yet another financial account under your name, and deposit money into it on your own.

The biggest difference between a Roth IRA and a Roth 401K is that you can invest the money in your Roth IRA account in whatever investments you want – you control the investment choices rather than your employer. So while your 401K might have a limited number of investment choices (typically big Stock and Bond Mutual Funds), you can invest your Roth IRA funds in individual stocks like GOOG (Google), Stock Mutual Funds, Bond Mutual Funds, REITs (i.e., Real Estate Mutual Funds), etc. And YOU get to decide which financial firm (e-trade, Vanguard, Charles Schwab) will hold your Roth IRA account, so pick wisely and choose the financial firm with the most investment options and lowest fees.

Like a Roth 401K, you can withdraw money from the Roth IRA account at any time, but you’ll end up paying taxes on a percentage of the withdrawn funds unless you wait until retirement age. So in general, you want to avoid withdrawing funds from your Roth IRA until retirement, unless you’ve got no other options.

So assuming you plan to save more than just what you can sock away in your Regular/Roth 401K, and assuming you make less than $124k/year, the first place to save your money is in a Roth IRA. You’ll get the tax benefits of a Roth 401K, but also be able to invest in any type of investments you like. But be forewarned, your best bet is to invest your Roth IRA money in a Large Cap Stock Index Fund – you’ll likely do much better than if you were to gamble by investing in individual stocks that you hand-pick.

Step #4: Take another 10-15% of your salary and invest it in a Large Cap Stock Index Fund (in a private account)

While it may seem like a lot of money to save, the $19.5k-$26k or so that you can sock away each year into your 401K/Roth IRA won’t provide nearly enough money for you to live a comfortable retirement! Nor will Social Security (if it’s still solvent when you retire). Unfortunately, if you want to live a comfortable retirement… or buy a nice house/condo, you’re going to have to save/invest even more of your money.

Since your 401K, Roth IRA and Social Security won’t be sufficient, I’d suggest that you open up a private investment account at a firm like Vanguard, and then take another 10%-15% of your overall salary (overall salary = the $100k your company pays before taxes are taken out) and invest these funds in a Large Cap Stock Index Fund like Vanguard’s Wilshire 5000 Fund (VTSMX) or Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index Fund (VFINX). If you want to spread your risk outside the United States, you could also buy an International Stock Index Fund (like Vanguard’s VGTSX), perhaps putting 85% of your money in American funds, and 15% in international funds. The mix is obviously up to you – international funds generally tend to be more volatile than their US counterparts, so they could bring a higher reward, but come with a higher risk.

When buying a Stock Index Fund, make sure to select a firm like Vanguard that offers “no-load” versions of these funds. No-load means that the firm doesn’t charge you a transaction fee to buy the fund’s shares. Some funds are loaded, meaning you have to pay a transaction fee (e.g., 3%-5%) every time you buy more shares of the fund. Imagine having to pay a $30 fee every time you invest another $1,000 - what a waste! With a no-load fund, when you invest a $1,000 of your money, $1,000 actually makes it into your account!

And, just as importantly, make sure the fund’s management fees are low – hopefully MUCH less than 1% per year. All Stock Mutual Funds charge management fees to pay the salaries of the fund’s employees, but these fees can vary widely. The most expensive funds can charge 2% or more per year, while the least expensive funds charge as little as .04%!! Skip the expensive funds – those fees will just eat away at your investment returns. I’ve mentioned Vanguard so many times because they have some of the lowest management fees in the industry AND they have no load (no transaction fees), so they’re an excellent place to open a private investment account.

In addition to purchasing a Stock Index Fund, you might also be considering buying individual stocks (e.g., Apple, Amazon or some hot new IPO stock). That’s OK too, but basically you should consider this as gambling. Never invest more than 4% of your private investable assets in any one particular stock, as enticing as that might be. So, for example, if you have $10,000 of total money to invest in your private account (don’t consider your 401K accounts), you could put up to $400 each in stocks like Google, Apple or Amazon. But as tempting as it may be to dump thousands of dollars into a hot new stock, avoid the temptation. Any single company can run into huge troubles – they can have a scandal, their latest product can be a flop, their sales can go down, or they may just be disrupted by an up-and-coming startup – and their stock can drop precipitously overnight (trust me). So if you do want to invest in some individual stocks, do so at your own risk and be careful. But do it for fun, not because you expect any skyrocketing stock prices.

By the way, the last point applies to your employer’s own stock too! If you work for a publicly traded company like Apple or Google, you’ll be given RSU shares (Restricted Stock Unit) as an incentive to join. RSUs are basically shares of your company’s stock, but they’re restricted so you can’t sell them all at once. Essentially your employer will give you shares of their stock over a period of 3 years to incentivize you to stay with the company. You’ll generally get 1/3 of this stock deposited into your account each year (with some shares removed to pay taxes) for you to do with as you please (this is called “vesting” – 1/3rd of your RSUs “vest” each year). Ideally try to limit the percentage of your company’s stock that you hold on to no more than 5%-10% of your overall private investable assets (not including the investments in your 401K/Roth IRA accounts). I know you want to be loyal to your company, but anything can happen to it – and if you have a big chunk of your money tied up in your company’s stock, you could lose it overnight! Ever hear of Enron? So as you receive more company-granted RSUs over time, sell some of them and re-invest the proceeds in a Stock Index Fund to ensure you don’t put too many eggs in your company’s basket.

When you invest in a private account and buy your Stock Index Funds, make sure to use an approach called Dollar Cost Averaging. Dollar Cost Averaging sounds complex, but in reality it’s really simple. Just invest the same dollar amount each month, no matter what happens to the stock market. So let’s assume you’re planning on investing $6k/year in your private investment account. Every month, regardless of whether the stock market goes up or down, just invest $500 (1/12th of your $6k investment funds) in your chosen investments. By taking this strategy, you’ll buy fewer shares when the market is more expensive, and more shares when the market declines and stocks are cheaper. This will average your overall risk and costs over time, since you’ll be averaging the amount you spend per share as the market moves up and down.

Now once you buy your investments, hold them. Avoid the temptation to sell them when the market starts declining, because that’s almost always a recipe for disaster. Just hold onto your investments for the long term, and again, if history teaches us any lessons, your average Large Cap Stock Index returns will be about 10-12% per year (vs. less than 1% in a typical bank account holding cash)! As much as it seems possible for you to “time” the market and decide the perfect time to sell and to buy, it’s a fool’s game – the professionals try to do it all the time and get burned. So why do you think you can do better? Not to mention that when you sell a stock or Mutual Fund at a profit to buy another, you’ll have to pay taxes on your gains, which gives you less money to put into your next investment. And who wants to do that. :)

Oh, and one more thing… If you make your investment decisions based on TV or radio shows, just beware… While these guys sound like professionals, their stock picks are statistically almost always horrible in the long run… Certainly far worse than investing in a low-cost Stock Index Fund. So again, consider professional picks from the radio or TV to be no better than gambling…

Step #5: When you’re ready to buy something big, move to cash

So now you’re on track to save loads of money. What should you do if/when you want to buy your first house?

Well, in order to get a loan from a bank/lender to purchase a house, you have to make a down-payment. A down-payment is an initial, large payment that you make to the house's seller from your own pocket, and it shows the bank that’s going to give you your home loan (a home loan is called a “mortgage”) that you’re serious about the purchase. Generally speaking, you’ll need to make a down-payment that’s 10% to 20% of the total purchase price of the home in order to secure a loan from a bank/lender. So if your dream condo costs $500,000, you’ll have to put down about $100,000 of your own money (with perhaps some thrown in from your folks) in order to get a loan for the other $400k. That down-payment ensures that if you somehow decide to stop paying your mortgage payments, and your house value declines (as it does in recessions/bubbles), the lending bank won't lose money if it has to resell the property.

So here’s what to do: Make sure to have enough money for your expected down-payment at least 6 to 18 months before you’re ready to buy your new home/condo. The stock market is quite volatile over the short term and your Stock Index Fund investments can swing wildly (dropping 40% or more during market crashes!). So about 6-18 months before you need cash to pay for a down-payment, sell off enough of your private investments (DO NOT sell your 401K or Roth IRA investments) to finance your down-payment and put the money in either a savings account or a Money Market Fund (which is pretty much the same as a bank savings account, but may pay a bit more interest). Both pay very little interest, but are “liquid,” meaning that you can withdraw money at any time for things like a down payment on a house, a new car purchase, etc. More importantly, their value won’t typically drop like stocks in the event of a market crash (technically Money Market Funds can drop in value, but it’s extremely rare). Don't forget - you're going to have to pay taxes on all of the gains you've made when you sell your private investments, so put aside the right amount of money for those taxes or you'll be in trouble come tax time!

Once you pick the right house and are looking for a loan, make sure to shop around with multiple banks/lenders. Often times, your real estate agent (the person who helps you buy the house) will recommend a lender that they trust to provide you with your loan. The problem is that these “trusted” lenders are rarely going to give you a good loan interest rate. These lenders often have business relationships with the real estate agent’s firm, and so your agent is simply going to recommend them whether or not their rates are competitive.

If these “trusted” lenders don’t think there’s any competition, they’re going to charge you a higher rate, meaning you’ll pay more every month for your mortgage. So be smart! Go to a website like www.lendingtree.com or www.bankrate.com and find out what interest rates they offer for the home loan amount you’re contemplating. These websites aggregate loans from literally dozens of different banks/lenders so you can easily find the lowest rate. You can then take the best loan rate you find back to your real estate agent’s “trusted” loan guy, and make him compete for your business. This could literally save you a few hundred to a thousand dollars per month, depending on your loan amount!

But be strong, the “trusted” loan guy (and perhaps your agent) will tell you that if you don’t use their firm for the loan, things will be more complicated and your purchase could be delayed and fall through. That’s BS – these other lenders that you will find on Lending Tree or BankRate only make money if they issue loans, and the more loans they “close,” the more money they make, so they’re highly incentivized to be efficient and competitive. And at a minimum, you should use them to negotiate your rate down even if you do decide to go with your agent’s “trusted” lender.

So how much should you be willing to spend in mortgage payments per year on a condo/house? Consider spending no more than 25% to 35% of your pre-tax income. So if you make $100k per year, you should consider limiting your mortgage payments to between $25k to $35k per year ($2k-$2.9k per month). Believe it or not, you’ll actually get a tax refund for part of the money you pay in mortgage payments each year (through the IRS’s mortgage interest deduction), so you could end up getting $2k-$4k or more of that $25k-$35k back at the end of the year after you file your taxes! This will potentially help you afford a slightly larger mortgage, so do the math before you go house hunting. On the other hand, owning your own condo/home is expensive: Every year, you'll have to pay 1.25% of your home's value in property taxes ($6,250 per year in CA! for a $500,000 home), about .35% of your home's value for home insurance ($1,750 per year), and up to 1% per year of your home's value in maintenance costs ($5,000 per year for things like painting, clearing clogged pipes, termite fumigation, etc.).

Two more things. First, it’s almost always better to get a fixed rate loan – one in which the loan’s interest rate won’t change over the lifetime of the loan. Variable rate loans are more volatile and if you’re not careful, your mortgage payment can skyrocket after several years! Second, it’s rarely worthwhile to take “points” on your loan (if you don’t know what “points” are, do some research – it’s unfortunately beyond the scope of this write-up) – especially if you intend to upgrade to a new, bigger home from your starter house after living in it for several years. So do the math before you buy points on your mortgage loan.

Finally, once you buy a house, you’ll probably have a large mortgage – one that will likely give you nightmares for several months. So before you buy, don’t forget to expand your emergency fund to cover your expected mortgage costs. That way you know if anything happens – you lose your job, your folks need some help, etc. – you’ll have yourself covered. And before you know it, that mortgage will seem small in comparison to your growing salary. Oh, and if you need to reduce your other investments to cover your mortgage, that can sometimes make sense. After all, your house will appreciate too (it’s a form of investment), so shifting your future investment contributions from Stock Index Funds to your home’s mortgage payment is a reasonable thing to do. Just make sure to consult a trusted friend or relative before you make any drastic changes to your investment strategy, and triple check that you have the savings and income to really afford a home.

Step #6: The above advice will last you 15-20 years, so you’ll eventually need to make changes

I’ve just given you a very aggressive investment strategy – I’ve basically told you to invest 100% of your investment money (minus your emergency fund) in Large Cap Stock Index funds. That’s considered the right thing to do for young investors with a long time horizon. Even if stocks plummet this year, if history is any guide, they’ll come back in a decade or less – and if you’re not retiring any time soon, you can wait out such “bear markets.” This strategy will historically deliver around 10%-12% per year in returns, much, much more than the .5%-1% you’ll earn if you save your money in a traditional bank account.

But as you get older – especially as you near retirement – this investment strategy will become increasingly risky. Why? Because stocks are super volatile and you don’t want to have 100% of your investment money locked into stocks right before you retire. Imagine you’re retiring next year and all of a sudden, the value of your investment portfolio drops 60% - what would you do? You’d have to delay your retirement for years until the market recovers. This could devastate your quality of life. So as you get older, it’ll make sense for you to diversify part of your investments into things like bonds (or Bond Mutual Funds), REITs, CDs, cash, etc. which have lower and more diversified risk.

When the time comes, you may need some help deciding how to best diversify your portfolio to meet your goals. You may want to hire an investment advisor to help. An investment advisor is a licensed “professional” who gives investment advice. Unfortunately, many investment advisors are not that objective, so you have to be super careful. There are two categories of investment advisors:

- Commission-based Advisors: Those that actively manage your investments for you (and take a 1%-2% “commission” per year, or charge transaction fees for every stock/bond purchase or sale). These advisors will recommend investments to you, then take a cut when you buy these investments or sell your old investments.

- Fee-based Advisors: Those that simply give you advice for an hourly charge/fee. You hire them, give them the details of your goals and your current investments, and then they give you advice. You then pay them only for the few hours they spend helping you.

Commission-based Advisors will cause you lots of heartache. Their primary incentive is to make money for themselves via fees, so they will maximize activities that generate revenue for them and their firms. They’ll recommend that you buy and sell investments frequently, since they get commissions every time you do so. And they’ll recommend you buy the Stock Mutual Funds that they work with, since they’ll get an under-the-table commission for every sale. And they often make money whether or not your investments do well! After all, if they charge a 1% fee, they get 1% of your portfolio’s value every year, whether it goes up or down!

On the other hand, Fee-based Advisors have no such incentives. They are paid an hourly fee for the short time they spend with you, and will not be compensated if you buy or sell stocks or bonds based on their advice. So they’re much more likely to give you objective advice since they won’t benefit from your investment actions after your consultation.

Be careful, though. Most investment advisors – even the ones paid hourly and with less incentive to rip you off – are mediocre. Frankly, you can often do far better by doing your own research on the Internet! Sites like Vanguard.com offer lots of tools to individual investors to help them figure out the right investment strategy given their current/future goals.

Background on Stocks, Mutual Funds and Index Funds

When I first graduated, I knew very little about stocks and mutual funds, so if you’re like me, the following sections provide a brief introduction to Mutual Funds and Index Funds. Read on if these topics are new to you.

Before I explain what a Stock Index Fund is, let me first explain what a Stock Share is, and then what a Stock Mutual Fund is.

What is a Stock? What are Stock Shares?

Every public company (e.g., like Microsoft or WalMart) issues N “shares” of stock when they go public – often N is in the millions or billions. Each share of stock entitles its buyer to 1/Nth ownership of the company. That’s right! By buying a share of stock, you are becoming a partial owner of the company! For example, if you buy one share of Apple stock, technically you own about one five-billionth of the entire company, since Apple has issued ~4.64 billion shares of its stock.

What is a Stock Mutual Fund?

OK, so what is a Stock Mutual Fund? A Stock Mutual Fund is a basically a corporation that has been formed solely to buy and hold a bunch of Stock Shares. The corporation accepts money from investors and then uses that money to purchase shares of one or more stocks (e.g., 1,000 shares of WalMart’s stock, 3,000 shares of Apple’s stock, etc.). For instance, I might form my own Stock Fund called Carey’s HighTech Fund and gather money from all of my former CS students, and then use the money to buy the stocks of each of the top-ten high-tech firms.

Just as Apple or WalMart might issue shares, a Stock Mutual Fund, like Carey’s HighTech Fund, issues shares of stock, too! So my HighTech stock fund might issue 1 million shares of its own, at $10 each. Each share entitles its buyer to 1/1,000,000 of the value of my fund. If my fund sold all of these shares, it would raise $10M dollars and could then use that money to purchase shares in each of the top 10 high-tech firms (investing $1M in each of the top-ten tech firms). So if you buy one share of Carey’s HighTech Fund for $10, you essentially buy $1 of ownership in each of the top-ten high-tech firms. If you buy 1,000 shares of the Carey HighTech Fund for $10k, you’ll essentially be investing $1k in each of the ten high-tech firms that the fund invests in. Now as each of these ten company’s stock prices goes up (e.g., Apple’s stock jumps from $100 to $200), the value of the Carey HighTech Fund goes up proportionally. So your share of Carey’s HighTech Fund stock that you bought for $10 might now be worth $11 instead. The value of the fund’s shares is basically directly correlated with the value of the Stock Shares the fund holds.

Typically Stock Mutual Funds have financial managers that pick and choose in which specific stocks to invest (Apple vs. Microsoft, GM vs. Tesla, etc.). These stock pickers earn a hefty fee to research the various stock choices and decide upon an investment strategy, and this fee is deducted from your investment in the fund each year. If the stock picker picks well, then perhaps your fund will do better. If he/she picks poorly, you’ll lose money. More on that in a bit.

What is a Stock Index Fund?

OK, so now we know what Stock Shares and Stock Mutual Funds are. What is a Stock Index Fund?

A Stock Index Fund is a special type of Stock Mutual Fund that uses a very simple investment strategy. Rather than having a super-smart manager that tries to pick promising stocks (by doing lots of research into a bunch of companies), the Stock Index Fund basically just picks an Index and buys the stocks listed in that Index.

So what is an “Index?” An Index is just a complex term for a list of stocks that was selected based on some simple criteria. For instance, the criteria might be “Include the largest 500 companies in the US” or “Include the 100 biggest technology companies in Europe.” For example, you may have heard of the S&P500 Index. The S&P500 Index is a list that includes the largest 500 U.S. companies (WalMart, Apple, GM, Ford, Boeing, Google, etc.). It's called a Large-Cap index because it is a list of really *large* companies like Walmart, Apple, Ford, etc. The Wilshire 5000 Index, another Large-Cap index, is a list that includes the largest 3,800 or so U.S. companies. The Russell 2000 Index, a Small-Cap Index, is a list that includes 2,000 smaller US companies. There are dozens of well-known Indexes, each focusing on a different area of the economy, or a different country.

So a Stock Index Fund is a Stock Mutual Fund that has picked a particular Index (e.g., the S&P500 Index or Russell 2000 Index), and then buys the shares of each of the companies listed in that Index. It’s a much simpler way for the Fund to decide what shares to buy, since it doesn’t require any complex research performed by high-paid stock pickers. It just takes the list and buys those stocks.

Moreover, because the Stock Index Fund invests in literally hundreds of stocks, you’re spreading your risk across hundreds of companies, so if any one company’s stock does poorly, another stock will likely balance it out. You’re hedging your risk.

Given that Stock Index Funds use such a simple mechanism to pick the stocks they hold, they generally have much lower fees than hand-picked Stock Mutual Funds, meaning you get to keep more of your money (and less goes to the stock pickers/managers).

Why do fees matter? Well, imagine if Stock Mutual Fund X charges you fees of 2% per year to pay their stock picker gurus. Now imagine that a low-cost Stock Index Fund Y charges just .5% per year, since its manager can easily decide what to invest in by looking at a publicly-posted list. Assuming funds X and Y invest in exactly the same stocks, after 20 years of investing with fund X, you’ll have at least 30% less than you’d have had you invested in fund Y. Why? Fund X charges 1.5% more per year than Fund Y, and after 20 years, that will result in a minimum 30% lower return (20 years * 1.5% = 30%). And the results will likely be even worse when you take compound growth into account!

If that weren’t enough to convince you to chose a low-fee Stock Index Fund, then how about this: If you picked 100 arbitrary Stock Mutual Funds (run by “genius” stock-picking managers), each year only about 20%-30% of them actually beat the gains you’d make if you just invested in a low-cost S&P500-based Stock Mutual Fund! That’s right! Even though these Stock Mutual Funds have genius stock pickers, they almost always do worse than funds that follow the popular Indexes! Those stock pickers could have done better selecting stocks by flipping coins! So save your money and pick a no-load Stock Index Fund with low fees.

Conclusion

So hopefully you now have an idea of how to start investing your money. Good luck! And always feel free to email me if you have any questions.

Oh, and if you found this write-up useful, don’t forget to pick up and read a copy of The Florentine Deception, my new techno-thriller novel. It’s available in e-book, paperback and audiobook formats. It’s a fun read and I’m donating all of my profits to charities benefitting students and veterans.

For more great financial advice from a former student, check out Devan Dutta's website. Also, you may find this glossary of terms useful!